Atomic Bomb: The Science and History Behind Its Power

▼ Summary

– In 1938, Enrico Fermi discovered uranium’s potential for chain reactions, leading to the Manhattan Project in 1940 to develop nuclear weapons before the Nazis could.

– The first sustained nuclear reaction was achieved in 1942 under the University of Chicago using the “Chicago Pile 1” reactor, confirming Leo Szilard’s theory.

– The first nuclear bomb was detonated in July 1945 in New Mexico, followed by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August, ending World War II.

– Nuclear fission splits heavy atoms, releasing energy and neutrons, while fusion combines light atoms under extreme conditions, as seen in stars and experimental energy projects.

– Atomic bombs use fission, but thermonuclear bombs (like the Tsar bomb) combine fission and fusion, creating vastly more powerful explosions with devastating thermal, shockwave, and radioactive effects.

The development of atomic weapons marked a turning point in modern warfare, combining groundbreaking physics with devastating real-world consequences. The journey began in 1938 when Italian physicist Enrico Fermi, then working in New York, identified uranium’s potential for chain reactions. Concerned about Nazi Germany exploiting this discovery, the U.S. launched the Manhattan Project in 1940 under Arthur Compton’s leadership. This secret initiative brought together brilliant minds like Fermi, Leo Szilard, and J. Robert Oppenheimer to explore nuclear fission’s military applications.

A pivotal moment came on December 2, 1942, when scientists achieved the first controlled nuclear reaction beneath the University of Chicago’s football field. Their makeshift reactor, dubbed “Chicago Pile-1,” proved Szilard’s theory correct. By 1943, Oppenheimer led the Los Alamos laboratory in New Mexico, where researchers designed and built the world’s first functional atomic bomb. Its test detonation on July 16, 1945, in the New Mexico desert paved the way for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki weeks later, events that forced Japan’s surrender and ended World War II.

At the heart of atomic energy lies the behavior of atomic nuclei. Atoms consist of protons and neutrons orbited by electrons. Under extreme conditions, nuclei can either fuse together (fusion) or split apart (fission). Stars like our sun rely on fusion, where hydrogen atoms combine to form helium, releasing immense energy. On Earth, scientists aim to replicate this process for clean power generation.

Fission, however, drives both nuclear reactors and atomic bombs. When unstable heavy atoms like uranium-235 split, they release energy and additional neutrons. If enough neutrons collide with other atoms, a self-sustaining chain reaction occurs. Nuclear reactors carefully control this process, while atomic bombs deliberately exceed criticality, ensuring each split triggers multiple reactions for an explosive release of energy.

Advancements led to even more powerful thermonuclear weapons. Unlike fission-based atomic bombs, these devices use a two-stage process. A primary fission explosion generates the heat and pressure needed to fuse hydrogen isotopes in a secondary stage. The Soviet Union’s 1961 Tsar Bomba test demonstrated this terrifying potential, producing history’s largest man-made explosion.

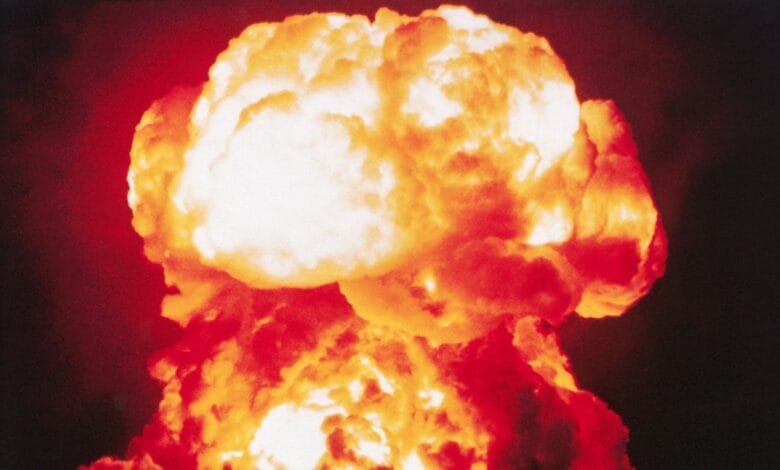

The iconic mushroom cloud symbolizes atomic devastation. Within seconds of detonation, a fireball erupts, emitting lethal neutrons and gamma rays. The blast’s thermal radiation ignites fires kilometers away, while the shockwave flattens structures. Most insidious is radioactive fallout, a toxic mix of fission products contaminating the environment for years.

Understanding these weapons requires grappling with both their scientific ingenuity and their catastrophic human toll. The same physics that illuminates stars also fuels humanity’s most destructive creations.

(Source: Wired)