Microsoft’s Glass Data Storage: Project Silica Explained

▼ Summary

– The world’s projected data generation of 394 zettabytes by 2028 is driving research into new, durable storage methods as current technologies like magnetic tape degrade over decades.

– Microsoft’s “Silica” system uses femtosecond lasers to encode data as tiny 3D voxels within glass, a material resistant to environmental damage, achieving a high density of 1.59 gigabits per cubic millimeter.

– A key innovation uses single-pulse laser writing to create two voxel types, significantly improving writing speed to 25.6 Mbps and reducing power demands compared to older multi-pulse methods.

– Testing suggests the data stored in glass could remain readable for over 10,000 years at high temperatures, far exceeding the longevity of conventional electronic storage.

– The technology is designed for long-term archival purposes, not everyday use, though scaling it up depends on reducing the current high cost of femtosecond lasers.

The staggering volume of data generated globally is driving innovation in archival storage, with Microsoft’s Project Silica emerging as a groundbreaking solution. This technology uses femtosecond lasers to inscribe information into glass, creating a durable medium capable of preserving data for potentially thousands of years. As projections suggest the world will produce nearly 394 zettabytes of data by 2028, the limitations of current magnetic tape and electronic storage become critical. These conventional methods degrade over decades, creating an urgent need for a more permanent archival format.

Scientists have long considered glass an ideal candidate for long-term data preservation due to its inherent stability. It resists damage from moisture, extreme temperatures, and electromagnetic fields. Earlier experimental approaches, however, struggled with practical issues like low data density, slow writing speeds, and high energy consumption. The recent breakthrough from Microsoft researchers, detailed in a scientific publication, directly tackles these historical shortcomings. Their system employs incredibly brief, high-power laser pulses to permanently alter the optical properties of glass at a microscopic level.

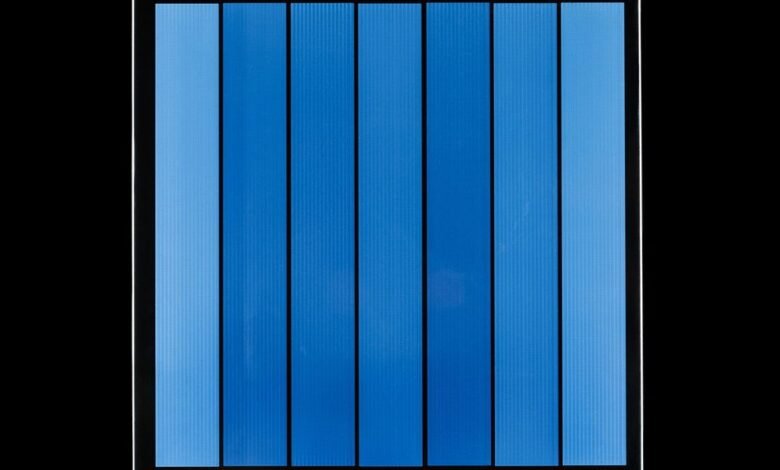

This advanced method encodes data as three-dimensional voxels, which are essentially the volumetric equivalent of pixels. Each voxel measures about half a micrometer in size and is strategically spaced within the glass substrate. An automated microscope, assisted by machine learning algorithms to correct for errors and interference, then reads the stored information. The resulting platform, named Silica, achieves an impressive storage density. A single glass platter, roughly the size of a drink coaster and only two millimeters thick, can hold up to 4.84 terabytes of data. This capacity is equivalent to archiving about two million books or five thousand high-definition films in a remarkably resilient and compact form.

A key innovation that boosts efficiency involves the creation of two distinct voxel types. Researchers developed both phase voxels and birefringent voxels, each requiring only a single laser pulse to form. Earlier techniques needed multiple pulses per voxel, which drastically slowed the writing process and demanded more power. By needing just one pulse, the laser focus can move rapidly across the glass surface. This advancement enables writing speeds reaching 25.6 megabits per second with a single laser beam, firing millions of pulses every second.

These voxels work by modifying the glass’s refractive index, which governs how light travels through the material. A phase voxel changes this index uniformly in all directions, while a birefringent voxel alters it in a way that depends on the light’s orientation. Birefringent voxels offer superior data density and energy efficiency but require high-purity silica glass. Phase voxels, while somewhat less dense, provide greater material flexibility and can be written into more common transparent substances like borosilicate glass, which is used in kitchenware.

To test the long-term viability of the silica storage, researchers subjected inscribed glass samples to accelerated aging tests. They repeatedly heated the plates to 500 degrees Celsius, simulating the slow effects of time at lower temperatures. The results indicate the data could remain readable for over 10,000 years at 290 degrees Celsius, and would likely persist for far longer under normal room-temperature conditions. This endurance radically outlasts any current electronic or magnetic storage technology.

It is important to understand that this technology is not intended for everyday computing. Project Silica is designed specifically for archival purposes, targeting data that must be written once and preserved for centuries. Obvious applications include safeguarding national library collections, irreplaceable scientific datasets, cultural heritage records, and cloud-based archives where information is retained indefinitely. The system addresses a common misunderstanding about glass, confirming that at standard storage temperatures, it is a stable solid and does not flow or deform over millennia.

While the potential is extraordinary, practical challenges remain. The femtosecond lasers required for writing are currently costly, raising questions about large-scale economic feasibility. The research team has openly shared their findings with the goal of encouraging broader scientific and engineering collaboration. They hope other groups will build upon this foundational work to help refine the technology and ultimately make permanent, high-density glass-based data storage a practical reality for future generations.

(Source: Spectrum IEEE)